Pectus Excavatum

Pectus excavatum is a congenital disorder which causes the chest to have a sunken or "caved in" appearance. It is the most common congenital chest wall abnormality in children.

What is the cause of pectus excavatum?

The cause of pectus excavatum is not known however it can run in families, with up to 25 percent of affected patients reporting chest wall abnormalities in other family members. Pectus excavatum occurs in approximately 1 out of 400–1000 children and is three to five times more common in males than females. This may be an isolated abnormality or may be found with other malformations including scoliosis, kyphosis, and connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome. The deformity usually becomes more severe as the child grows.

Some children with pectus excavatum report that they have chest pain and shortness of breath or limited stamina with exercise. Other children have no symptoms. Surgery may not alleviate chest pain.

What is the outcome for a child with pectus excavatum?

Historically, pectus excavatum was incorrectly considered as only a cosmetic defect. However, recent studies have revealed that children with significant defects also suffer from heart and breathing difficulties. The sunken chest restricts the volume of the chest and keeps the lung from expanding fully. Lung capacity may be reduced which can result in children having difficulty tolerating exercise or strenuous activity.

The sunken chest can also constrict the heart, reducing blood flow and heart function. These effects on the heart and lung can be measured and are reversible by correcting the sunken chest. It is important to note that these effects on the function of the heart and lung are not life-threatening and that individuals with pectus excavatum can live a full and normal life.

Some patients also suffer psychologically and emotionally as a result of the disorder. Although many patients are able to live comfortably and happily with the deformity, many other patients struggle with negative body image, low self-esteem, and social awkwardness. This is especially true for teenagers as the pectus defect often worsens during the adolescent years, a time when the child may be seeking peer acceptance.

How is pectus excavatum typically treated?

Pectus excavatum does not require any treatment. The condition does not present a danger to the child. Surgical repair is an elective procedure and requires insurance approval before proceeding. Repair is typically done in the teenage years, once the pubertal growth spurt is underway or completed. If repair is done before puberty during childhood, there is a risk of recurrence during adolescence. The deformity is not repaired in very young children. Since surgical repair is optional, talk openly and honestly with your child about the condition to determine how this is affecting their health and well-being. The psychological impact can be significant to some children.

There are two types of surgical correction, open repair (aka Ravitch Procedure) and minimally invasive repair with a metal bar (aka Nuss Procedure). Both are done with general anesthesia and require an inpatient hospital stay of 5–7 days.

The majority of the patients with pectus excavatum are candidates for the Nuss procedure. However, the decision for the patient to undergo a Ravitch or Nuss procedure will depend on the degree of the pectus deformity, the age of the patient, and ultimately will be determined by the surgeon.

Open Repair (Ravitch Procedure)

Open repair, called the Ravitch procedure, is done through a horizontal incision across the mid chest. In this repair the abnormal costal cartilages are removed, preserving the lining of cartilage, thus allowing the sternum to move forward in a more normal position. This procedure takes approximately 4–6 hours. In certain patients, an osteotomy (a break) in the sternum is done to allow the sternum to be positioned forward. In addition, to keep the sternum elevated in the desired position after the removal of the cartilages and the osteotomy, a temporary metal chest strut (bar) may need to be placed.

Minimally Invasive Repair (Nuss Procedure)

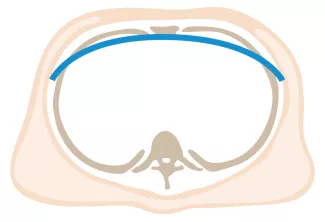

Repair with a metal pectus bar, called the Nuss Procedure, is achieved by bending a stainless bar to fit the chest wall. The bar is then inserted and secured through a small incision under each arm using the aid of a endoscope to monitor and avoid injury to the heart during insertion. The bar goes over the ribs and under the sternum, to push the sternum forward into the new position. The ends of the bar are secured to the chest wall. This procedure takes between 1–2 hours.

Related Video

- Hospitalization for Pectus Excavatum

- Risks and Complications for Pectus Excavatum

- Pectus Excavatum Patient Interview

What is needed preoperatively?

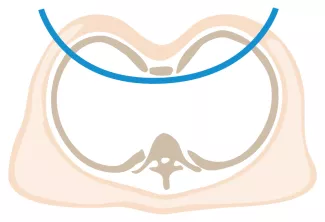

Preoperatively, your insurance carrier may require a CT scan to measure the Pectus Severity Index (PSI, also known as the Haller Index), which is the the ratio of the width of the chest wall to the depth at the deepest point of the deformity. This value usually must exceed 3.2 to be considered severe enough to be surgically corrected.

For more information on the safety of CT scans please visit UCSF Imaging: AQs for Your Pediatric Radiologist

Often, a pulmonary function study and cardiac evaluation (echo or cardiac stress test) are required as part of the preoperative evaluation in order to receive insurance approval. These studies can be ordered by your pediatrician, so they can be done close to home. If the surgeon evaluating your child is concerned about an undiagnosed musculoskeletal disorder, a consultation with a specialist will be required prior to surgery. Your child’s surgeon will discuss this with you during the clinic appointment. If your child has a metal allergy, a titanium bar will be ordered. This bar must be ordered in advance of the operation since it cannot be bent in the operating room by the surgeon.

Care in the hospital following surgery

The surgical repair of pectus excavatum is a painful procedure. Length of stay in the hospital is determined primarily by pain control.

Anesthesia and care at time of surgery

At the time of surgery, an epidural catheter will be placed in your child’s back for continuous local anesthesia and will stay in place for several days. While the epidural is in place, a urinary catheter will drain urine from the bladder. An intravenous (IV) catheter will be inserted for giving fluids and IV medications. Sometimes nasal oxygen is needed and sometimes the surgeon will place a tube to drain fluid from the surgical area. All of these therapies are temporary and will be discontinued when no longer needed, usually before discharge.

Day following surgery

Your child will be expected to get up out of bed and walk the day following surgery and will need to practice deep breathing to keep the lungs healthy and prevent pneumonia.

Constipation

Constipation is a common problem for children on narcotics. Laxatives will be started in the hospital and should be continued, as needed, at home after discharge.

Hospital discharge

Children will be discharged when they are comfortable on oral pain medication, are eating and drinking without difficulty, and have no fever or signs of an infection. If a surgical drain was placed at the time of the operation, your child may go home with the drain in place. The nursing staff will teach you how to take care of the drain while your child is at home. The drain is usually removed at the first clinic visit.

Homecare after surgery (Ravitch or Nuss)

Patients who have a Ravitch procedure without a chest strut are seen only as needed after the first postoperative appointment. Ravitch procedure patients with a chest strut or Nuss procedure patients with a bar are seen at least annually after the first visit. The strut or bar is expected to stay in place for 2-3 years.

- A shower can be taken 5 days after surgery. Have your child take the clear film dressing off before the shower and leave the tape strips in place. These will fall off on their own.

- There are no stitches to be removed. These are under the skin and dissolvable.

- Narcotic pain management may be required for up to one month after surgery.

- Constipation is a common problem, and daily use of laxatives while on narcotics is recommended.

- Redness or swelling of the incision(s) should be reported as soon as noted.

- If you child is discharged with a drain in place, it will be removed in the surgical office when the draining had stopped.

- Children who have a pectus bar should call the office for any trauma to the chest, pain or numbness of the arms, or pain that is not relieved by oral medications.

- Sports may be resumed as soon as the surgeon determines this is safe. Some contact sports may be not be permitted while the bar is in place. The bar may prevent adequate chest compressions during CPR and defibrillation requires paddle adjustment to be effective.

- No MRI should be done while the Pectus bar in in place.

- Physical therapy may be helpful in improving posture.

- Use of a medical alert bracelet or necklace is recommended at all times in order to notify emergency providers of the presence of a Pectus bar. Recommended bracelet text: Steel bar in chest. CPR more force. Cardioversion ant/post paddle placement.

Pectus Excavatum Patient Story Video

Interview with a patient about his experience with Pectus Excavatum and the surgical repair he got at UCSF Pediatric Surgery that corrected it.

Towards a better solution, the Magnetic Mini-Mover Procedure

Both of the Ravitch and Nuss procedures require big operations and hospitalization for pain management. The fundamental problem with both techniques is that they attempt to correct a significant rigid chest wall deformity all at once, i.e., in a single surgical procedure. Perhaps a better principle for correction of chest wall and other deformities is by gradual (bit-by-bit) correction using minimal force applied over many months. This is the same principle used in moving teeth with orthodontic braces.

In an effort to overcome these problems, we have developed a novel method of achieving gradual deformation/reformation of chest wall cartilage without the need for insertion of painful orthopedic devices or repeated surgeries. We call this new technique the Magnetic Mini Mover Procedure (3MP).

Learn more about the Magnetic Mini Mover Procedure